If it wasn’t for the high price of sea cucumbers, considered a delicacy in China and Southeast Asia, one of the greatest shipwrecks of the Tang dynasty (which ruled China from 618-907 AD) would still have been undiscovered. In 1998, fishermen diving for sea cucumbers off the coast of Belitung, a small island east of Sumatra in Indonesia, discovered ceramic bowls in the soft sandy sea bed. Realising that these were of value, the fishermen sold the bowls and the location of the find. A German company then obtained the requisite permits to salvage the location and were lucky to find a ship laden with a cargo that was almost intact, albeit covered in coral and marine life. Over the next few months, the contents of the shipwreck were salvaged and put up for sale with the condition that the entire cargo would be sold as a whole rather than piece by piece. After some bargaining, a Singaporean foundation bought the cargo for US$ 32 million in 2005 and is now exhibited at the Asian Civilisations Museum.

$32 million might seem like a high price but the Belitung shipwreck was groundbreaking in two major ways - one, it provided proof of direct trade between China and the middle east as early as the 9CE and second, it brought to light the ingenious ship building technique of Arabian Dhows. Studies are still underway so the shipwreck might still have more mysteries to uncover.

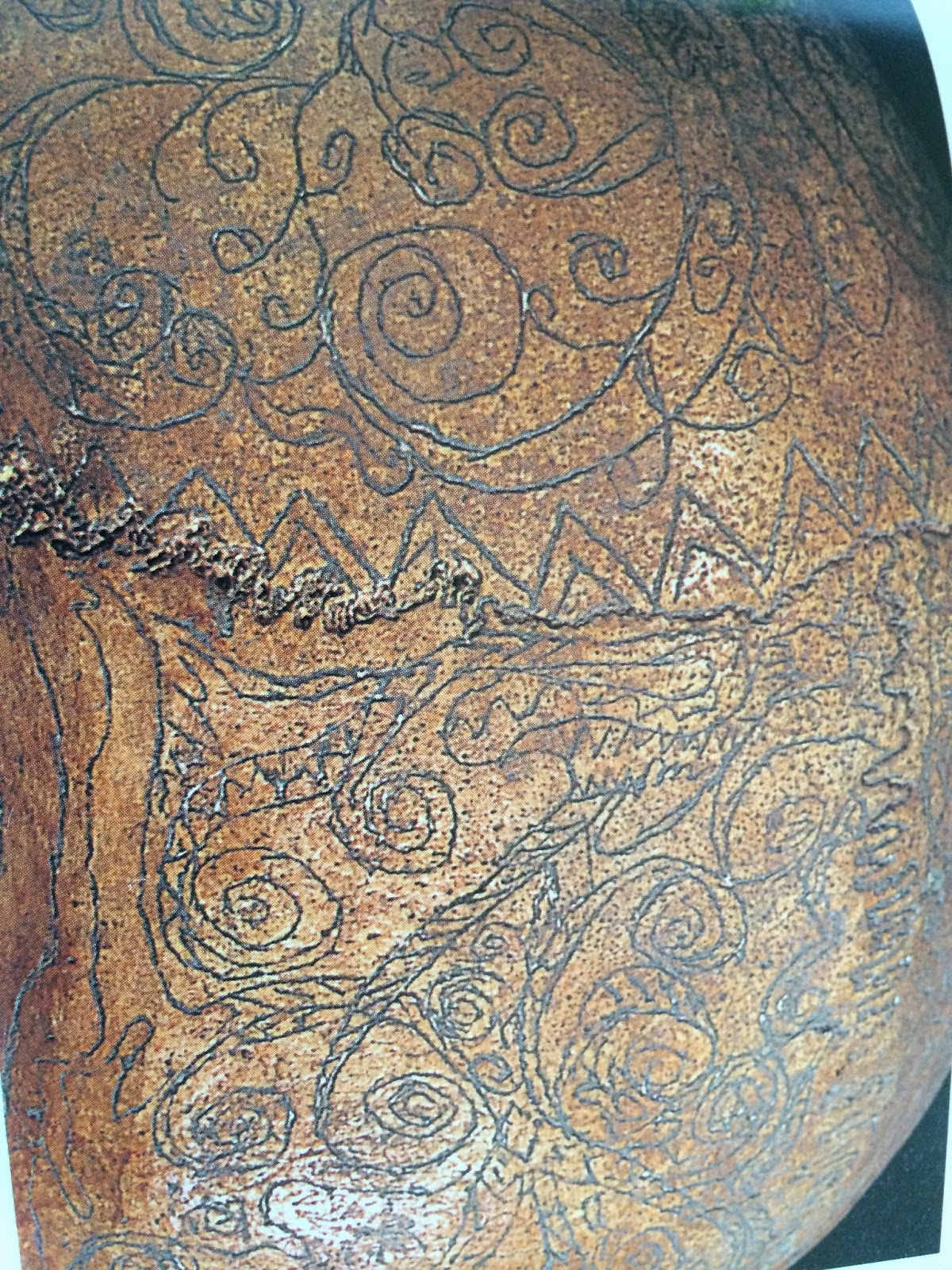

If you were to look at the exhibits today, you would hardly believe the state they were in when salvaged. Salt water can be very corrosive and being underwater for centuries, the cargo was a host for various marine-life. Immense conservation work had to be done in order to bring this cargo back to its pristine state. After salvaging the cargo, most of it was shipped to New Zealand and stored in a warehouse for conservation. The precious pieces were worked on by an unlikely crew of dentists - a profession in which steady hands are a prerequisite to dealing with delicate materials in confined spaces.

|

| Fig 2: Coral encrusted ceramic jar |

Carbon dating of some organic items on board (ship’s timber, shipment of star anise and a small piece of resin) and inferences made by scientists has dated the shipwreck to about 830AD, which would mean that she has been lying mostly undisturbed in the sea-bed for about 1200 years. 830s was the period of the two great empires- the Abbasid Caliphate in western Asia and the Tang dynasty in China. There are writings mentioning trade and diplomatic ties between these empires with their capitals in the cities of Baghdad and Xi’an (of the terracotta warrior fame) as early as 7CE but this shipwreck provided concrete proof of their connection.

Ships from the middle east have been sailing the waters around Asia and it was evident from the construction of this ship that she was a traditional Arabian dhow. She was built of African wood and the planks were tied together with coconut fibres without the use of nails or screws. Similar technique of ship-building were used in the middle east until very recently.